The UK market fell in the first part of August but it has subsequently recovered and is not far off the high it reached at the end of May. There has been some quite mixed news for the market to digest over the last couple of months, including a particularly high level of negative geopolitical developments with problems in Ukraine, Iraq and the Middle East continuing. Meanwhile, on the economic front, the Chinese economy is slowing and large parts of the Eurozone continue to flirt with deflation and recession. More positively, inflationary pressures in much of the western world remain under control (thanks partly to China’s slowdown and the resultant fall in commodity prices) and leading indicators in the US economy look strong, not least thanks to lower oil and gas prices feeding through to improving disposal income for the US consumer.

Dividend Growth

Ben and I do not aim to make big predictions or bets on the macro-economic or geopolitical environment. Instead, we aim to insulate the Evenlode portfolio from these uncertainties by owning a group of resilient, globally diversified stocks that tend to be good at generating high levels of cash and dividends through thick and thin.

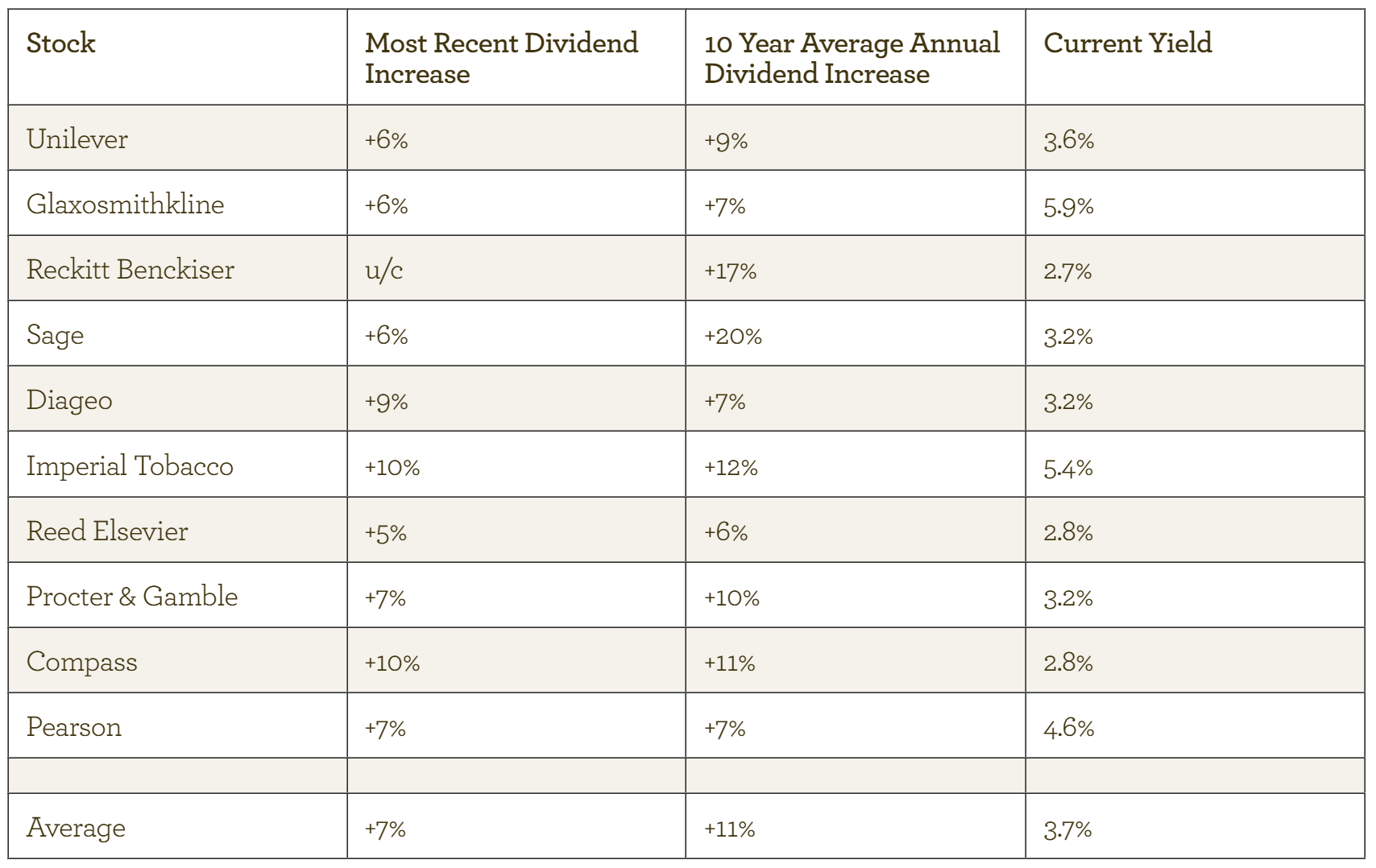

In this context, the first half results season has now been and gone, and it’s reassuring that in aggregate Evenlode holdings have continued to make incremental progress despite an environment that hasn’t been all plain sailing. Importantly, dividend growth has been healthy, despite a six month period where the stronger pound created a significant headwind for the earnings of UK listed global companies. The table below shows the fund’s current top ten holdings, and details the most recent dividend increase, as well as their long-term dividend growth rates and current yields*.

As mentioned in this month’s factsheet GlaxoSmithKline and Diageo released disappointing second quarter results, though as can be seen above continue to increase their dividends at a good rate. Elsewhere results have been solid and reassuring, and cash generation remains healthy. The average free cash flow yield for the ten stocks above is a little over 6%, comfortably in excess of current dividends. This is genuine excess cash - after interest, tax and investments made for future growth. It therefore takes into account the heightened level of investment that several large positions in the portfolio are currently making (most notably in the consumer branded goods sector). It is worth stressing that these reinvestments remain small relative to the average company in the market as our process leads us to asset light companies with limited capital requirements. However, relative to their own histories, companies such as Unilever, Reckitts, P & G and Diageo continue to reinvest more than normal as they build out their emerging market footprint, despite the recent slowdown in these markets**. These investments take the form of, among other things, marketing, advertising, distribution networks, manufacturing facilities, inventory and human resources.

The Plough Back

In old school Wall Street vernacular this reinvestment is referred to as the plough back, and it comes with a short-term cost. Much of this spend impacts current earnings and all of it impacts today’s free cash flow. An interesting thought experiment is to imagine a private equity company getting hold of a Unilever or a P & G and running it to maximise short-term cash-flow. Run on this basis these companies would chuck out spare cash and trade on far higher free cash flow yields than the current 5-6% level they trade at. Short-term investors might be more attracted to this mode of management, but it would risk underinvestment in the future. Ploughing cash back into the business today lays down a runway for the long-term opportunity, which remains very significant. Spend per capita on most repeat-purchase consumer goods in emerging markets continues to increase, but still represents only 10-20% of the level found in developed markets. And over time investment levels will reduce as a percentage of revenues as they are spread over an increasingly large sales base. This provides the potential for gentle profit margin expansion over time. We like businesses with this capacity to suffer in the short-term for the long-term health of the franchise. Not all reinvestment decisions will, of course, prove sensible with the benefit of hindsight. But as time goes by, reinvestment in diversified businesses with good micro-economics tends to average out to a very satisfactory result.

This trade off between the short-term and the long-term is evident in other sectors of the portfolio too. In the media sector Pearson is currently making a heavy ‘plough back’ relative to history (in this case partly to expand into emerging markets, but much more significantly to accelerate its transition towards a digital business model). This is coming with a clear short-term cost, as CEO John Fallen described earlier this year:

It may have seemed less risky on the face of things to not do the restructuring and investment, and we could have seen profits continue to rise nicely year-by-year in the short-term. But we think the far greater risk would be not to grab this opportunity. It is designed to take on the big structural changes in education, not least the transforming power of technology, which is a challenge, but is also a much bigger opportunity for Pearson if we can successfully embed ourselves with our customers.

Reed Elsevier has been on its own different but analogous journey away from physical publishing over the last few years. As demonstrated by recent results, Reed is now beginning to reap the benefits of this shift. Last month I also mentioned our software holdings (Sage, Microsoft, SAP) and their transition to an increasingly cloud-based, subscription model. This transition continues to require a heavy ‘plough back’, but even so earnings growth and free cash flow for all these holdings remains high.

Elsewhere, in the healthcare sector, no one liked Astrazeneca a couple of years ago. The company was widely despised in 2012 when newly arrived CEO Pascal Soriot announced a cancellation of the share buy-back in favour of investment in building its pipeline through research, development and in-licencing. Only now are investors beginning to appreciate the value of these investments and Astra’s maturing pipeline, particular in the area of cancer therapies. More generally, ten or fifteen years ago investors were much more comfortable attributing value to the R & D investments made by pharmaceutical stocks, and the sector traded on a much higher valuation. Today, sentiment has swung to the opposite end of the spectrum. As a result, these stocks trade on far more attractive valuations and dividend yields.

To sum up, there is always a trade off between generating cash-flow today, and putting cash back into a business for the future. Our preference is for highly cash generative companies that can make this plough back while still having plenty of excess cash flow left over, even when they are funding the heavier phases of their investment cycle. These stocks tend to reward you with both dividends today and steadily compounding cash flows (and therefore dividend growth) in the future.

Hugh Yarrow, Investment Director

21 August 2014

Please note, these views represent the personal opinions of Hugh Yarrow as at 21 August 2014 and do not constitute investment advice.

*Source: Canaccord Genuity Quest, Wise Investment. Unilever dividend growth in Euros

**For instance, Unilever’s capex to sales ratio has been at the 4-4.5% level over the last few years, compared to a historical average of 2-2.5% level. While it still remains very low relative to the average company, it represents a very significant pick up in relative terms. Over time management expects this level to drift down as the effect of scale and thereby operating leverage in emerging markets.