Outlook 2013

People change their mood quickly, particularly when investment markets are involved. As I write, the UK market has risen approximately +18% since the end of May last year. At that point, financial markets were struggling to see the positive side of anything, all talk was of impending collapse in the Eurozone financial system and a global recession, bonds were in fashion and stocks were decidedly out of fashion.

Now, only slightly more than six months later, the mood is far more upbeat. The global economy has been in a sort of 'goldilocks' sweet spot over the last few months - not too hot, not too cold - with a combination of improving leading indicators and benign inflation sounding the all clear for investors. Predictably, following a rise of this magnitude in the stock market, animal spirits have returned. This month's Merrill Lynch survey suggests that the average fund manager currently has their highest allocation to shares since February 2011, and fund manager confidence in the global economy is at its highest since April 2010 (a call for temperance, if ever there was one!). The key cyclical risk to this current benign backdrop is the threat of rising inflation. As I have said before, the post-crisis world is leading to shorter business cycles and with interest rates at close to nothing, the key moderator of the business cycle has become inflation. Just as the recoveries of 2010 and 2011 stalled due to a bubbling over of inflationary pressures, the risk is that the current recovery goes the same way. Inflation warning indicators are already starting to flash.

Despite the recent cyclical upswing in the business cycle, the fundamental structural backdrop has not meaningfully changed over the last six months and all the same major risks that we faced at the start of 2012 remain unresolved. Government indebtedness in most parts of the world remains at very high levels, and deleveraging headwinds continue to drag on the trend level of global economic growth. Meanwhile, the Eurozone’s deep-rooted structural problems have not been addressed – liquidity can only do so much to help. Elsewhere, although the cyclical outlook for China looks better now than it did six months ago, the basic issue there (an over-reliance on fixed capital formation) still remains.

Sticking to our knitting

These risks are all worth taking seriously (just as they were a year ago), but they do not change our basic investment approach. As I said last January, we ‘prepare for the worst and hope for the best’. We look for resilient high-quality businesses that can suck these risks up and cope, increasing shareholder value through thick and thin.

In my view, one of the most positive things about the investment world today is that there are still so many very obvious risks to worry about. This has created a moderating influence on most stock valuations over the last three years (notwithstanding the recent market recovery) that is no bad thing for the truly long-term investor. Quality stocks don’t need an upward revaluation to provide a decent return to shareholders. If a stock starts the year on a 3.5% dividend yield, grows its dividend by +8% over the year, and still ends up on a 3.5% yield, it has given investors a total return of +11.5% without getting more expensive (almost precisely what Procter & Gamble, for instance, has done over the last twelve months). This is a sustainable return which borrows nothing from the future. Many of the highest quality franchises in the world continue to trade on 3% or 4% dividend yields, and these dividends should be capable of healthy growth over the next decade. This is the subset of our investable universe that currently interests us the most - in contrast, many of the small and medium sized stocks we follow are out of range for now.

The Incrementalists

“The best thing about the future is that it comes one day at a time”

Abraham Lincoln

Another benefit of owning high-quality, financially strong stocks is their ability to steadily adapt to changing conditions - to a large degree, they shape their own destiny. The management of these businesses have the luxury of thinking longer-term, and laying down investments for the future even when times are not so good.They are the 'incrementalists' of the stock market. One day at a time, they steadily invest to drive future cash-flows higher*. Below are three recent examples of this process at work:

Incrementalist case study 1: Unilever

Take Unilever’s ‘Pure It’ brand. Pure It water filters are made by Unilever’s Indian business and are also sold in several other countries including Brazil and Indonesia. Unilever’s CEO Paul Polman recently commented on the company's significant investment in this brand:

“The Pure It brand could be a $1 billion brand in the future, but we won’t make a margin on it for 5 to 10 years. Every penny of revenue will be invested in expanding the number of users – giving as many people as possible clean water at home. Some will say that is margin dilutive in the short-term. I will say ‘fine - it is’. But am I going to deny clean drinking water to 100-200 million people without any cost to the business? What kind of an investor is that? What kind of a world is that? And when you give them the Pure It brand, you find they start buying lots of other Unilever products.”

It is refreshing to observe such long-term thinking in a publicly listed company. Many management teams, faced with a share price that wobbles around on a minute-by-minute basis, struggle to look this far out.

Incrementalist case study 2: Domino Printing

We have recently re-initiated a holding in Domino Printing, a company that manufactures and services printers for best-before dates, bar codes and batch numbers on repeat purchase goods such as packaged food, beverages and healthcare products. Domino’s industry is consolidated and evolves very slowly, but over time new technology comes along and Domino have a track record of successfully adopting and developing these technologies. But this does not happen by itself – it requires a persistent acceptance of the need to invest in longer-term projects, all the way through the industry's cycle. So Domino maintained a steady commitment to research and development in the 2008-9 downturn And last year, despite having a tough year due to a slowdown in new printer sales, Domino’s management have kept their eyes firmly on the longer-term, increasing R & D by +9%. Over the last three years, R & D investment has now increased 45% . This growth in investment, though a short-term drag on results, will play an integral part in the group’s competitive position over coming years.

Incrementalist case study 3: IG Group

IG Group is a global market leader in retail financial derivatives. This business is quite steady but tends to be somewhat countercyclical – they do well when financial asset volatility is high and less well when volatility is low. Given the recent drop in volatility to a five year low, their industry is now in a downturn. But as CEO Tim Howkins pointed out this month at IG Group's interim results, their market position is creating an opportunity to take share in the downturn as they continue to invest when others can't:

“In these markets we really see the benefits of our scale and our profitability, and that’s in contrast to our competitors who are feeling the pain rather more than us. That’s certainly something we are capitalising on”

Clearing one-foot hurdles

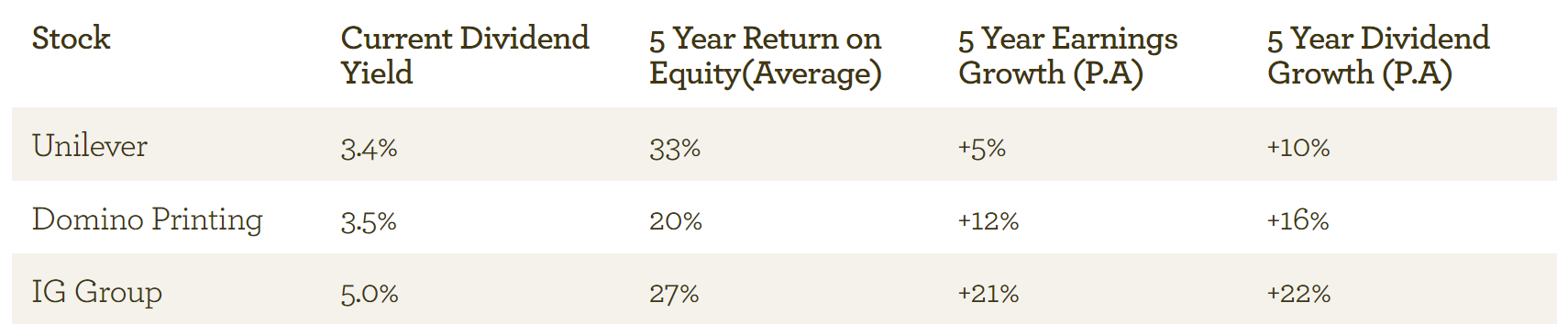

In summary, we have a strong preference for management teams that allocate their capital with a view to long-term sustainable value creation, rather than short-term results. And we are most attracted to businesses that have the market position and financial strength to continue to do this, even when times are tough. The longer term benefits can be seen in the results of the three high-return companies I mentioned above (over what has been by no means a straightforward period for the global economy)**. The strong grow stronger:

This incrementalist approach is undeniably less exciting that many other investment styles and when animal spirits are rising, as they have been over the last few months, it may seem unnecessarily austere and conservative. But if we avoid taking big risks and remain invested in this way, the portfolio's long-run returns should look after themselves. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger refer to this approach as 'clearing one-foot hurdles':

"After 25 years of buying and supervising a great variety of businesses, we have not learned how to solve difficult business problems. What we have learned is to avoid them. To the extent we have been successful, it is because we concentrated on identifying one-foot hurdles that we could step over rather than because we acquired any ability to clear seven-footers."

Hugh Yarrow

18 January 2013

Please note, these views represent the personal opinions of Hugh Yarrow as at 18 January 2013 and do not constitute investment advice.

*Rio Tinto, with its recent $14bn write-down of previous acquisitions, is a reminder of how hard some businesses find it to invest with an incrementalist view. This is a good case study on why we avoid resources stocks. Some will blame the management, but spare them a thought - it is hard to allocate capital consistently well in a commoditised and highly cyclical industry, with a business model that relentlessly demands huge capital outlays to drive future growth. As I wrote in October 2009 (An Eye On Inflation): "“[For commodity producers] the positive impact of rising sales is quickly offset by escalating spend on costs, capital expenditure, and acquisitions to replace depleting resource bases. Look no further than Rio Tinto’s 2007 Alcan acquisition for a case study. Surplus cash flow, rather than returning to shareholders, was channelled into new resources at inflated prices. As a result, the only shareholder reward for years of strong commodity inflation was a dividend cut and a rights issue.”

**Source: Cannacord Genuity Quest.