We often talk about the activity in the Evenlode portfolio when we communicate with our co-investors, whether face-to-face, through our writings and tweets, or via our video blogs. It’s interesting to talk about the things that we’ve done, but those who have engaged with us will have gathered that we are in fact long term investors. That being the case, at the portfolio level we don’t engage in that much activity over short time frames. In this investment view I’d like to explore some high-level aspects of our investment process to give a sense of when and why we engage in portfolio activity, and how the process naturally limits the amount of trading that goes on. Valuations are key, and I’ll touch on the current valuation environment at the end.

Turning things over, slowly

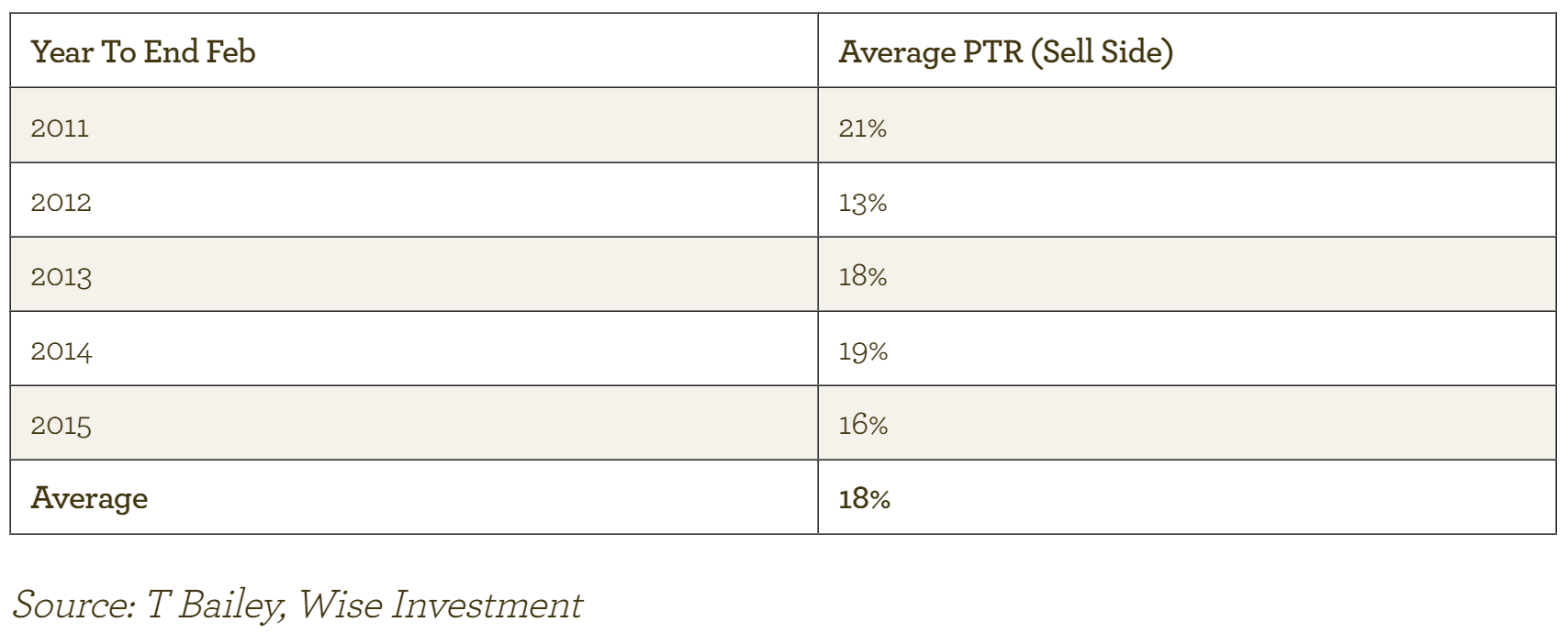

The amount of time Hugh and I spend talking about our portfolio activity can make it feel like our turnover rates are frenzied, but the reality is much more sedate. For example, in the year ended February 2015 the sell-side turnover rate* in Evenlode Income was 16%. That implies an average holding period of over 5 years. The history of the fund to date has shown a turnover rate consistently in the teens with one year in the low 20s, as shown in the table below, so our process has led to a consistently low turnover measure.

At the most basic level, we believe in investing in quality companies, not trading share prices. We have written much about quality in the past, and will do so in the future as well, so I won’t dwell on the details this time round. Taking that basic tenet as read, we consider ourselves to be investors of the buy-and-hold persuasion.

The value leg, or taking opportunities as they arise

That said there is another leg to our investment process. Quality is one, and value is the other, i.e. we are also ‘value investors’. The market sometimes offers us opportunities to buy on suitably cheap valuations, or sell at attractively expensive prices.

In between times we’re happy to hold on and let the companies we invest in do the work for us. But the very fact of us being value aware means we accept a degree of activity in the portfolio. This enables us to both take valuation opportunities, and manage valuation risk, an additional risk-management ‘belt’ to the ‘braces’ of investing in quality companies.

Long term valuations, not short term noise

Our valuation approach is, though, long term in nature. We value companies based on a very long stream of free cash flows we might get from them. These companies, having been assessed as exhibiting the characteristics that make up our definition of ‘quality’, are given credit for creating long-term value for shareholders in our valuation model. But we’re very much aware that valuing equities cannot be done with a great degree of accuracy, and by making a range of estimates of free cash flow, we estimate how wrong we might be as well.

Not being able to accurately value a stock doesn’t, to us, mean that one shouldn’t try, particularly for the sorts of firm we want to invest in at Evenlode. But it does have some implications for how our analysis works in and of itself, and also how we manage the portfolio.

In valuing a company using a stream of cash flows over 20 years or more, one year’s results are not going to move the firm’s net worth that much. So if a firm slows down for a couple of years, Unilever in emerging markets say (to give a recent example), it might reduce our estimates a bit but we’ll see that in the context of a pretty fuzzy valuation ‘band’ anyway. So unless there’s a really significant shift in the business model, the results in any given year alone are unlikely to change our outlook too much.

A relative lack of sensitivity to a single set of results is a benefit to the buy-and-hold approach. If our valuation framework bounced around too much in response to those bad (and indeed good) periods, we might end up trading rather more than we would like. That would incur costs and not allow the companies to do the long-term work for us.

At a fundamental level, we’ve constructed a fuzzy way of looking at valuation that will help us to engage in portfolio activity when valuations are stretched in either the expensive or cheap direction, and not do anything much otherwise. For us, that balances our desire to be long-term stewards of companies with making the most of the market opportunities. It is also suitably counter-cyclical; it will push us to invest when prices are low even when our quick-thinking emotional brains might baulk at a suddenly depressed share price. Similarly, while we want to hold on to winners when the future returns remain acceptable, we are aware that a great business can become so expensive that the firm’s quality is unlikely to ‘shine through’ the high price. The valuation framework pushes us to sell in that situation, and not be beholden to any one company come what may.

I’ll re-emphasise: The buy and sell happen at the extremes of valuation. In between is a range wide enough to accommodate holding on to companies, in keeping with the acknowledgement of being unable to put a precise number on a stock price. It’s worth noting though that we are not saying we will be able to call the top or bottom of a stock price; having a valuation discipline does not mean we can control the stock market or are in possession of a crystal ball. Prices can and do move a long way in either direction, for protracted periods of time.

What we do do

When the valuations start pushing us in a direction to increase or decrease a weighting, we do things incrementally. Each week we meet and examine the investment evidence we’ve collected. Have there been any fundamental changes to business models? What are valuations looking like? Is there a reason to move a weighting?

In many weeks we won’t do anything at all, and sometimes that extends to months. Monday after Monday, we analyse and yet sit in the same portfolio positions. That’s really what we do – analyse businesses, analyse valuations, consider in the context of our predefined investment criteria, repeat. That’s the real activity. What happens in the portfolio is a result of that process, and much of the time it isn’t anything at all.

We must sometimes do something though, otherwise the turnover rates above would be zero. When a valuation starts to look enticing on the buy or the sell side, we engage in a process we call the ‘nudge’. Again, being realistic about the accuracy of our valuations and our ability to time the market, we build into or out of positions gradually. If we had more certainty, we might make big bets, creating or annihilating whole positions with one phone call or mouse click. But that is not our modus operandi.

As a result of the process described above, if a stock we own is starting to look a little expensive, we’ll take a little out of the position. If its price rise continues, we’ll move a little more out. And so on. Sometimes the price rise doesn’t continue and our activity will end, and sometimes it goes on for so long that we exit a position entirely. A similar process happens when we see what looks like an attractive price for increasing a weighting as well.

The nudge allows us to be long-term owners and stewards of the companies we invest in, whilst balancing the risks and opportunities that valuation can present to our co-investors.

What we’re doing right now

Let’s get out of the abstract and into the here and now. There’s much interest in the level of market valuations, with new price territory being reached in indices on both sides of the pond. Our framework gives us a window onto the valuation environment.

Our chosen measure of value is what we call the ‘forward cash return’ on offer from a stock. This is analogous to a bond’s redemption yield**, so the higher it is, the ‘cheaper’ the stock.

The universe of stocks has on average entered the top end of our ‘fair value’ estimate***. That means that the companies that we look at are, on average, pretty well pitched in terms of price. Within that there is clearly a range of valuations from the expensive to the cheap.

Right now we are able to construct a portfolio from the cheaper stocks, which as a whole is trading at an attractive absolute valuation. As I mentioned, the back end of 2014 and early 2015 saw a bit of activity on the trading front, so we have worked to ensure value is retained.

On the sell side of the activity was a response to some of the companies we examine getting a bit more expensive. We lowered our positions in Compass and Reed Elsevier, and reduced Novartis and Smith & Nephew so much that we exited them entirely. Replacing them were some new positions – Spectris, IMI, Paypoint, Weir Group, Informa, Mitie and Domino Printing (Domino from a low base, and soon to be exited as it has received a takeover offer).

That period of heightened activity has now tailed off, and the chart above shows that we can be happy with the current valuation shape of the portfolio. The environment is certainly not as attractive as it has been earlier in the history of Evenlode Income, but on an absolute basis there are still value opportunities to be had.

Conclusion: A look to the future

We think that valuations are perfectly acceptable right now, but just because we think they are ok, it doesn’t mean that we think the only way is up. As things develop in the market in the future, we’ll look to make the most of any opportunities that arise. Low commodities prices have thrown up a few buys in the form of Spectris, IMI and Weir for example, and perhaps it’ll be some other macroeconomic event that does the trick. Maybe the UK election will cause some volatility. Whatever the cause, our process will show us the way to activity if we think it is justified, otherwise we’ll be observing, checking and repeating. That’s what we really do.

Ben Peters, Investment Director

22 April 2015

Please note, these views represent the personal opinions of Ben Peters as at 22nd April 2015 and do not constitute investment advice.

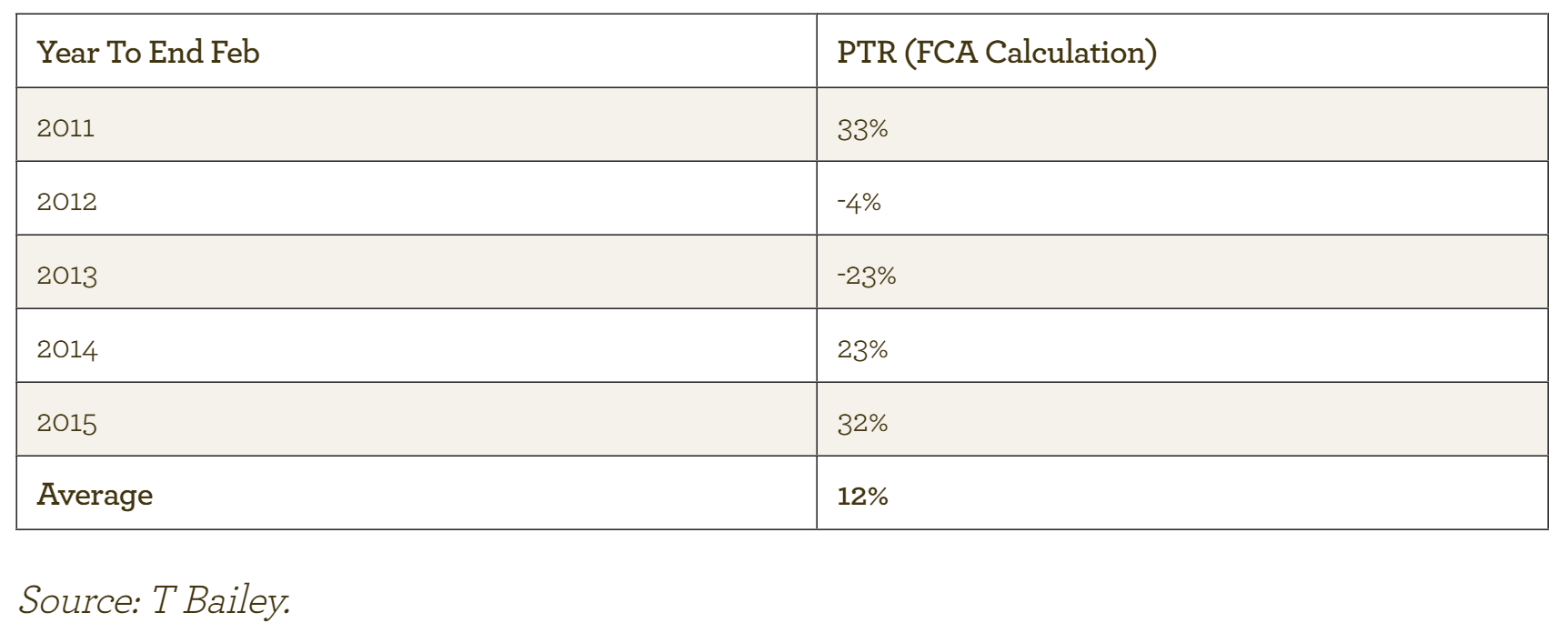

*The sell side turnover rate is calculated as the total sales in the portfolio divided by the average portfolio size in a given year. The FCA also mandate a calculation, which has lead to somewhat nonsensical negative rates as in the table below (even when it works it double-counts the turnover rate, so all should really be divided by 2):

**We take the future cash flows from our valuation model and allow the current market price of the stock tell us what the implied discount rate is. In fact (for those who are interested) we calculate this at the enterprise level and solve for the WACC, which we deconstruct to find the cost of equity.

***This is a real framework, and 6-7% real is roughly what developed market equities have delivered over the long term historically.