As time goes by, market volatility matters less and less and fundamentals matter more and more. As Benjamin Graham put it, the market is a voting machine in the short-term but a weighing machine in the long-term. Capital growth is like a tuning fork that fluctuates around the more steady progress of fundamental dividend growth (with, in the above chart, some particularly big fluctuations during the austerity of the 1950s, the great inflation of the 1970s, and the technology boom of the late 1990s). But as time goes on this ‘noise’ reduces and it's dividends and dividend growth that become the main drivers of return*.

Less Stuff, More Dividends

The same can be said for individual stocks. For most shares, if you lay the long-term dividend record alongside the stock's performance chart, there's likely to be an increasingly high correlation as time goes on. And it's not surprising. Dividends are the last and most important bit of the equation for shareholders, paid from any spare cash left after all other outlays have been made, including any capital expenditures needed to drive future growth in the business. They are also the only tangible thing that finds its way back to your bank account in return for your original investment - they are genuinely capable of putting food on the table.

In the spirit of these considerations, our aim is to put together a portfolio of highly cash generative shares that provides both a decent dividend yield today and prospects for higher than average, inflation-beating dividend growth. If dividends can rise like this then share prices should follow, even if a bit of patience may be required along the way.

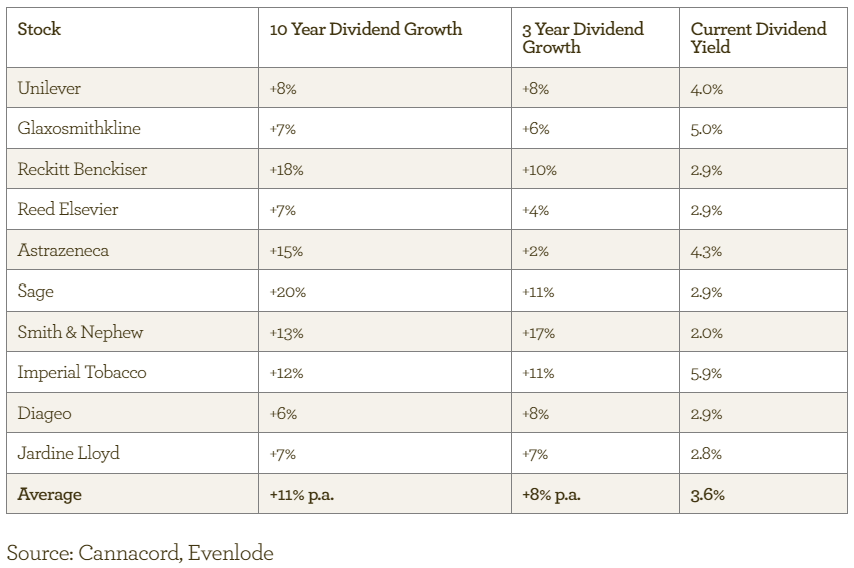

A snapshot of Evenlode's current top ten positions gives a flavour of the ability of the fund's holdings to crank out long-term dividend growth. Average 10 year dividend growth has been +11% per annum for these stocks (compared to a dividend growth rate of +5% over the same period for the overall UK market) and although the rate of growth has slowed (not surprisingly) since the global financial crisis, it remains at a still respectable +8% per annum over the last three years.

What unites all these holdings is their asset-light business models. They possess few physical assets relative to their profitability but instead are rich in intangible assets - normally a complex web of intangible assets that have built up over many years including brands, embedded knowledge bases, research and development expertise and distribution networks. As a result, these businesses don't need to buy much more 'stuff' each year to drive future growth. This is a crucial characteristic for us. It means there is plenty of spare cash left over for shareholders each year which can be used for four main things, all of which help long-term compound returns:

1) Dividends.

2) Special Dividends.

3) Buying back shares.

4) Buying other businesses.

Reckitt Benckiser is a good example, with its portfolio of brands from Dettol to Nurofen to Durex. Brands such as these represent the ultimate intangible asset. Used as a short-hand for making quick, safe decisions, customers buy these products based on perceived value rather than production cost (a man standing in a chemist’s condom aisle is a particularly good example of a consumer eager to make a quick, safe decision, and not a particularly price sensitive one at that!). This pricing power leads to very high profitability relative to the amount of 'stuff' (factories, machines etc.) needed to produce and distribute Reckitt's products. As a result, Reckitt is currently only spending about 11% of its cash-flow on on buying assets to maintain and grow it's business organically (i.e. capital expenditure)**. All the rest of the remaining cash-flow is 'spare' - left over for shareholders to do what they want with. Reckitt's +12% dividend growth per annum over the last 15 years is testament to the power of this economic model long-term.

Other asset-light industries that we tend to gravitate towards include the technology, media and healthcare sectors. Sage, for instance, is currently spending only 7% of its cash-flow on buying assets to maintain and grow the business, Reed Elsevier 24% and GlaxoSmithKline also 24% . Like Reckitt, these companies just don't need to spend much of their profits on 'stuff' to generate growth***.

Staying The Course

It is worth remembering these fundamental micro-economic factors when Mr Market is fixated with the latest concern of the moment - a great example in today's market being worries over emerging market currencies. For the long-term investor, the man standing in the condom aisle (or equivalent loyal shopper) is likely to be a far more important factor for long-run compound returns than what the Argentine Peso or the Venuezuelan Bolivar is up to this week.

Take Diageo, for instance, another business rich in intangible assets. They released somewhat lacklustre results last month with a slowdown in emerging market regions, and shares fell accordingly. But thinking long-term, the strength of Diageo's brands and business model means it can ride out this volatility and emerge in good shape. CEO Ivan Menezes pointed this out at the time of their results:

We've been managing emerging market volatility in Latin America and Asia for a long, long time. One of the great strengths of Scotch whisky is our ability to handle and manage pricing and margins through volatility. Look at the waves of crises we've ridden in Brazil, in Venezuela, in Argentina over the last 15 years, for example. The approach we take is to stay focused and invest in building the brands, while managing the business to recover pricing and margins through the volatility. If you look at the 15 year trend we've grown market share, improved margins and premiumised the business as we've gone through it.

And perhaps more significant than words was the +9% increase in Diageo's dividend. As management put it:

This growth rate reflects our confidence in the business and the fact that we continue to see the medium-term growth in the business as attractive.

Finishing where I started off, there is nothing quite so powerful as a high quality share offering a decent dividend yield today and potential for good growth in the future. While the market rise over the last two years has made it more difficult to find value, the current disinterest in some of the highest quality names in our investable universe means we are able to hold large positions in some great businesses, and still meet our dividend aspirations. Investors are increasingly looking elsewhere for their excitement but we think Diageo, with its combination of a 3% dividend yield and +9% dividend growth, represents a great example of this opportunity.

And as with Guinness, good things tend to come to those who wait...

Hugh Yarrow, Investment Director

17 February 2014

Please note, these views represent the personal opinions of Hugh Yarrow as at 17 February 2014 and do not constitute investment advice.

*The UK market yielded 3.8% in 1945 and finished the period on an only slightly changed dividend yield of 3.6% (the data here is up to the end of 2012). Dividend growth at +7% per annum therefore almost entirely accounts for the capital growth over the period. Adding the initial dividend yield of 3.8% to this +7% growth rate is approximately equal to the annualised total return over this period (which is +11% per annum).

**All reinvestment figures quoted in this piece are capital expenditure on tangible and intangible assets relative to net cash inflow from operating activities, excluding money spent on business acquisitions. Taken from latest full year financial results in each case.

***While aiming to bias the portfolio towards companies that consistently produce cash-flow, we also aim to avoid companies that consistently consume cash-flow. Examples of these asset-heavy companies include manufacturers, airlines, oil and mining producers, house builders, plant hire companies and utilities. They might make as much profit as an asset-light company, but if they are aiming to grow in the future, they'll need to take a large chunk of that profit and reinvest it straight back into the business (BP and National Grid, for instance, are currently spending 116% and 90% of their respective cash-flows on capital expenditure). Charlie Munger summed it up with the following quote:

"There are two kinds of businesses: The first earns twelve percent, and you can take the profits out at the end of the year. The second earns twelve percent, but all the excess cash must be reinvested – there’s never any cash. It reminds me of the guy who sells construction equipment – he looks at his used machines, taken in as customers bought new ones, and says, ‘There’s all of my profit, rusting in my yard.’ We hate that kind of business."